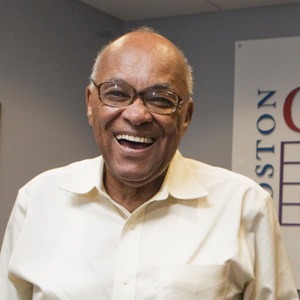

Hubert Jones didn’t need another project.

For five decades, he built and nourished nonprofit organizations that spoke to one of this country’s most enduring struggles: race. He had served as dean of the Boston University School of Social Work for 16 years, the first African-American in that role. He was already a hero to many in Boston, a city with a history of racial tension.

But during a trip to Chicago, Jones was moved by something he didn’t expect. Watching a performance of the Chicago Children’s Choir, it hit him.

“Just about that time I was beginning to understand that the arts were the best way to bring young people together across racial, ethnic and social class divides,” Jones recalls. “And here it was, bang, right in my face.”

There are children’s choruses all over the country, of course, but Chicago’s was different because it was diverse. Jones, “a voracious consumer of music” from Beethoven to Baez, saw creating a similar organization in Boston as a way to contribute to social healing and community building.

“We had a very tough time after school integration started in 1974,” says Jones. “We’re beyond most of it, but there are still vestiges.”

From that 2001 performance in Chicago, Jones felt driven to create the Boston Children’s Chorus. The goal: to unite young people across differences of race, religion and economic status. Children age 7 to 18 who might not necessarily have any contact with each other come together – literally – in harmony.

The chorus, which is funded by foundations, government, corporations, individuals and tuition, has grown from 30 students since its start in 2003 to about 400 today. Its Martin Luther King Day concerts are televised nationally. The choirs have traveled across the country and as far away as Mexico, Japan and Jordan. Choir members, and there have been 1,500 of them over the seven years, praise its power in their own lives.

“It was a huge part of my life for my entire high school career,” says Georgia Halliday, 19, a music education major at New York University who started with the chorus when she was 13. Last year Halliday went on the Jordan tour and vowed to return to the country. This summer, she’s working there as an English teacher.

“It’s all because of that tour and because of how passionate Mr. Jones is,” says Halliday. “He’s such an idealist. You tell him anything you want to do and he’s like, ‘Go for it.’ If you said, ‘I want to fly to Mars,’ he’d be like, ‘Go for it. I’ll make some phone calls.’”

That’s classic Hubie Jones.

Jones credits his father for sparking his drive toward social change. The elder Jones belonged to an all-black staff of porters for the Pullman Co., which manufactured and operated railroad sleeping cars, and he was active in the porters’ union. Jones remembers his father introducing him to A. Philip Randolph, the president of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, one of the country’s top black leaders.

“A. Philip Randolph was a very strong voice concerning civil rights,” Jones recalls. “My father used to refer to him as `The Chief,’ and he took me to meet him when I was in college. That was a major thing that shaped my commitment to having a voice on matters related to social justice.”

Another turning point for Jones came when he saw Martin Luther King speak in Boston. “Dr. King walked to the podium without any notes and out came this extraordinary oratory laced with philosophy, history, you name it.”

By that time, Jones was working toward his master’s degree in social work at Boston University, and King’s words struck him hard. “I was so pumped up by what I had heard,” Jones remembers, “so enthusiastic, so elated.”

Jones took his background and influences to shape a long, distinguished career as an academic and a social entrepreneur.

“Frankly, when I decided to retire from Boston University, I got into a panic because I could not see where this would take me,” he recalls. “I knew that I would not have a normal retirement, whatever that is.”

He didn’t.

Jones remained active as a senior fellow at the University of Massachusetts Boston and later as special assistant to the college’s chancellor for urban affairs. Meanwhile, he continued to mentor young social entrepreneurs.

“Other people have ideas, but Hubie actually makes them happen,” says longtime collaborator Charlie Rose. “He doesn’t sit back and wait for someone else to do it. He’s impatient with the status quo, and he’s able to make things happen in a really dramatic way.”

Rose is vice president and dean of City Year, a national nonprofit that helps young people spend a year serving their communities. In 1987, he and Jones were both founding board members at the organization, where Jones now holds the title of social entrepreneur in residence.

“Hubie is the conscience of Boston,” Rose says. “He has an ability to get you to think about a challenge, an initiative or a response to something that brings out the absolute best in you.”

Jones plays that role with members of the children’s chorus, too. He asks them about school, future plans, whatever. During a recent rehearsal, the kids shouted a big “Woo!” – excited to see him.

Though the rehearsal was occasionally lighthearted, buzzing with laughter and the chatter of friends, preparing for a performance is serious business. As the students practiced for a tour that would take them, within the span of a week, to Philadelphia, Maryland and Washington, D.C., they were poised and intense. Their song list ran from spiritual (“Elijah Rock”) to soulful (“Lean on Me”) to patriotic (“America the Beautiful”), with ballads in the mix (“Somewhere Over the Rainbow”).

Such professionalism, Jones says, is well orchestrated. “There are a lot of people in the music world who take the position that there’s no way that young people can sing at a level of excellence. And that gets blown away.”

The quest for excellence guides the chorus in many ways, not just in music. The children and teens must audition for the chorus, which is divided into nine different groups based primarily on age and skill. At all levels, the singers are taught to exhibit self-confidence, be good citizens and develop diverse relationships.

Close to a third of the chorus’ children are from the suburbs, the rest from Boston or Cambridge; 45 percent come from households with incomes of $50,000 or less. Thirty-five percent of the members are white, 43 percent are black, 8 percent are Hispanic and 6 percent are Asian. The rest are a mix.

“While the kids say it’s not about race, unfortunately race is something that’s very visual,” says David Howse, the chorus’ executive director. “We open the dialogue about race and so many other things they deal with.”

Jones plans to continue the dialogue by remaining involved with the chorus as he launches yet another project. Last year, he started Higher Ground, a program inspired by the Harlem Children’s Zone, Geoffrey Canada’s initiative to keep children and their families on the right path with social, educational and community-building services.

Jones says you have to know which opportunities to embrace because they’re going to push you closer to your goals and which to turn down because they’ll divert you from your mission.

“Opportunities will come along that you can’t even imagine,” he says. “When I started the Boston Children’s Chorus, if I had said, ‘Hey, you know what? We’ll have a national television broadcast within four years of this little choir we’ve put together,’ they’d have had me locked up.”