Peek Inside

Here’s the introduction to How to Live Forever: The Enduring Power of Connecting the Generations. Reprinted with permission from PublicAffairs, a division of the Hachette Book Group.

Extensions

Extensions

Getting things done on time has never been my strong suit. Twenty years ago I wrote my first book about getting older. The writing process, to say the least, was difficult. As the publisher’s deadline neared, my anxiety became paralyzing. I spent day after day in front of a blank monitor, unshaven, pajama clad, increasingly disheveled, searching the web for distraction.

One day on a perverse whim, I went to Amazon and typed in the title of my book, only to discover that the manuscript I’d yet to start writing was already for sale. In a stupor of sleep-deprived insanity, I clicked the “Order Now” button. Maybe this was all a bad dream. If I selected overnight delivery, perhaps the next day I’d wake up to a UPS parcel rescuing me from the nightmare. The package never arrived.

I’m still not quite sure how that book got done. (Or this one, for that matter.) But I do know that my history of procrastination didn’t start with these authorial woes.

I was already showing a talent in this area as an eighteen-year-old college freshman. In September of 1976, I drove ninety minutes from our house in Northeast Philadelphia to the leafy campus of Swarthmore College. I wasn’t remotely ready for the rigors of higher education, especially those of the academic sweatshop my chosen institution would turn out to be.

The first in my family to attend such a demanding place, I was singularly unprepared. My father was a gym teacher turned school administrator, and my mother had gone to college for a year before dropping out. I attended a large, working-class public high school with six thousand students, including eighteen hundred in my graduating class. But I came of age at a time when even private higher education was far more accessible and affordable than it is today. My first year, the cost of tuition, room, and board at an Ivy League school or a private liberal arts college was about $6,000, total. Even kids like me whose parents didn’t have the resources to help pay for a university education could scrape by on financial aid, work-study, and modest loans.

“By the time I’d made it, academically bloodied and beaten, to the break between the semesters of my sophomore year, I had probably set something approaching an intercollegiate record for incomplete classes.”

I was, from the outset, headed for failure. I tried basing my inaugural paper, “Introduction to the Old Testament,” largely on the CliffsNotes edition for the Bible. My professor was unimpressed.

By the time I’d made it, academically bloodied and beaten, to the break between the semesters of my sophomore year, I had probably set something approaching an intercollegiate record for incomplete classes. I’d racked up nine by that point—impressive, if I do say so myself, considering that I’d only taken twelve courses and that four of them had been pass-fail.

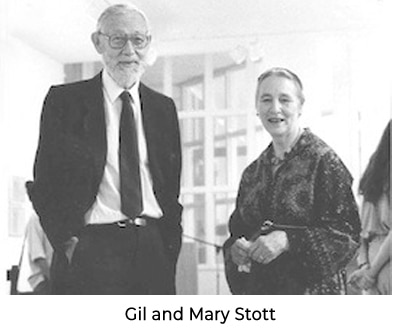

As it turns out, there was a silver lining in all this failure. I desperately needed more time to finish assignments, and the school, in its wisdom, required only three steps to get an incomplete approved. The first was asking for one, the second was getting the professor to say yes, but the third required institutional approval, in the form of sign-off from the school’s associate provost, an office held by a silver-haired, scraggly-bearded sixty-three-year-old named Gilmore Stott.

Gil Stott had himself come from modest means, something that likely contributed to his abundant empathy for struggling students like me. A kid from Indiana, he’d gone to the University of Cincinnati in the 1930s, excelling academically and earning a Rhodes Scholarship in part for completing a trans-Canadian canoe and bicycle trip with sausages tied to his back for sustenance.

Get your copy now!

During World War II, Stott served as an intelligence officer to General George Patton and fought in the Battle of the Bulge, winning the Bronze Star. This part is hard for me to imagine, given Stott’s soft-spoken, utterly gentle demeanor, the opposite of Patton’s blustering bravado. At Oxford’s Balliol College, he studied philosophy, which led to a PhD from Princeton. After graduate school, Stott held positions in the Rhodes Scholarship organization and became the right-hand man to Frank Aydelotte, head of Princeton’s famed Institute for Advanced Study during its heyday.

On the side, Gil served as Einstein’s personal driver and confidant.

When Aydelotte became Swarthmore’s president, Stott accompanied him, serving as an ethics professor and later as dean of admissions. He was a source of calm and a trusted bridge between groups during the turbulent times of the 1960s, when the college’s charismatic president, Courtney Smith, died of a heart attack during a student takeover of the administration building. Gil chaired the Upward Bound program at the school, helping bring low-income students from nearby Chester to campus, where young people became acquainted with college life and received guidance to help prepare them for higher education.

A lifetime long-distance runner with a shockingly slow gait (it was almost like he was running in place), Stott was a thin, handsome man with smile lines at the corners of his eyes. I remember him clad in the tweed jacket you’d expect from a liberal arts college dean, along with an unexpected bolo tie, as if to say, “I’m not quite as buttoned down as you might think.”

After my nine formal visits to his office to request incompletes, plus informal ones to request extensions of incompletes and more just to see the man, he took me under his wing, as did his grandmotherly administrative assistant, Etta Zwell. Together Stott and Zwell had a kind of Batman-and-Robin operation going, focused on bringing young people like me into the fold.

Whenever Gil could make out my slumped, dejected figure shuffling down the long corridor to his office with another request to buy some time on one course or another, he got a bemused smile on his face. He would grant me the extension, then invite me over for dinner—as would Etta. They became my family away from home, like surrogate grandparents.

Whenever Gil could make out my slumped, dejected figure shuffling down the long corridor to his office with another request to buy some time on one course or another, he got a bemused smile on his face. He would grant me the extension, then invite me over for dinner—as would Etta. They became my family away from home, like surrogate grandparents.

As part of the extended Stott family, I was exposed to a whole new world for someone who had grown up in a Levittown-like housing development and gone to a vast, homogeneous high school. One summer, I traveled with Gary White, an African American student from Philadelphia and the center on the school’s football team (the Little Quakers), to spend a week with the Stotts and other guests at their rustic retreat on Parry Island, several hours north of Toronto. For Gary and me, this was our first camping trip. On the way up, he taught me how to drive a stick shift.

Parry Island in the late summer was a shimmering vision of harmony, literally. Gil, a devoted cellist, and his violist wife, Mary, played in string quartets on the porch most evenings, accompanied by their violin-playing children—or one of the loose collection of students like me who were constantly coming and going. Back home, Gil and Mary age-integrated the college orchestra by joining it. According to his obituary, Gil added violin to his repertoire and took his last violin lesson the day before he died in 2005, at ninety-one.

“For all his official roles at the college, Gil’s truest title might have been tender of wayward students and their souls.”

For all his official roles at the college, Gil’s truest title might have been tender of wayward students and their souls. The formal role he held mattered less than his eye for young people who were stumbling. And his main tools weren’t advice and a wagging finger. He was a quiet man, so quiet that even if he was inclined to give advice, it might have been inaudible. What came across clearly was a blend of acceptance and love. Each of us felt that Gil was completely in our corner. And he was.

When I graduated, thanks in no small measure to Gil’s support, I was elected to give the commencement address with my friend and former roommate Charlie McGovern. We dedicated the address to Gil, in part out of affection and also out of a sense that he wasn’t fully given his due. We saw that despite Gil’s importance in so many lives, he didn’t have a fancy office or a lofty title.

In that concern, I think we were mistaken. Our dedication at graduation produced, to our surprise, a spontaneous, sustained, and thunderous standing ovation. A measure of the man’s life. It was likewise a credit to the college’s leaders that they recognized the value of such a role and provided the perch for Stott to carry it out while an employee and for two decades further after he “retired” in 1985. Today, a portrait of Gil Stott playing his beloved cello hangs in the entry of the main building of the college, in guardian angel–like fashion.

Still, even brilliant mentors can only do so much; I made a grammatical error in the first line of my speech.

KIDS VERSUS CANES

Now I’m just about the age Gil was at the time we first met, which is remarkable to me. Then again, the idea that he would live thirty more years beyond his sixtieth birthday, twenty of them after formally retiring from the college, is testimony to the possibilities of extending life spans. Today, thanks to gains in longevity and the aging of the baby boom generation, ten thousand people turn sixty-five every day. By 2060, a quarter of the US population will be over sixty-five.

Perhaps even more significant, for the first time in our history, we now have more older people than younger ones. In 2016, for example, there were 110 million adults over fifty and only 74 million young people under eighteen, a trend that is here to stay.

“The graying of America is understandably worrying for a country that has always prided itself on its youthful spirit and makeup.”

The graying of America is understandably worrying for a country that has always prided itself on its youthful spirit and makeup. Academics and pundits alike predict that this demographic shift will have adverse effects on the prospects of young people, ushering in cross-generational conflict, zero-sum wrangling over scarce resources between “kids and canes,” and a vast generation gap. Many worry about the so-called gray/brown divide, a gulf between a largely white older population and a much more diverse younger group.

Christopher Buckley provides a satirical solution to all these problems in his novel Boomsday—mass euthanasia for the gray-haired set, sending baby boomers off to the great beyond at seventy, to the betterment of all who remain. But even in the realm of satire, there’s a glitch. A New Yorker cartoon depicts a pair of native Alaskans shaking their heads over a consequence of climate change—insufficient ice floes for dispatching the boomers.

The increase in the number of older people in America is paralleled by an increase in the needs of our kids. Today half of all public school students come from low-income families—and 80 percent of low-income kids aren’t reading proficiently by the end of third grade. We’re not making much of a dent in the child poverty rate or the educational achievement gap based on race and ethnicity. More children of color are getting to college, but not nearly enough are finishing. And social mobility is increasingly limited—42 percent of children born to parents in the lowest income bracket stay there as adults.

And yet we move forward as if our future weren’t at stake. Those in power cut programs that feed, care for, and educate children; degrade the planet these young people will inherit; and saddle future generations with record debt. How can we find the will to realign priorities in a nation where children don’t vote and older people do? Where are we going to find the resources, both human and financial, to cover the costs of an aging America and invest more in young people at the same time? If we don’t, will we knowingly continue to sacrifice our children?

In 2014, two distinguished sixty-something boomers sounded the alarm. Stanley Druckenmiller and Geoffrey Canada embarked on a college tour not to figure out where to send their children but to alert young people that their futures were being compromised. The goal: to be modern-day Paul Reveres, waking up the next generation to the transgressions of their own.

In 2014, two distinguished sixty-something boomers sounded the alarm. Stanley Druckenmiller and Geoffrey Canada embarked on a college tour not to figure out where to send their children but to alert young people that their futures were being compromised. The goal: to be modern-day Paul Reveres, waking up the next generation to the transgressions of their own.

The two crusaders were both students at Maine’s Bowdoin College in the 1970s, although they didn’t know each other at the time. Druckenmiller went on to generate a sizable fortune working with George Soros and then with his own firm, Duquesne Capital Management. Canada made his mark creating the Harlem Children’s Zone, one of the most successful and significant efforts to improve the lives of children (Druckenmiller served as the Children Zone’s board chair). In 2009 the Chronicle of Philanthropy selected Druckenmiller as the most charitable man in the country.

Canada and Druckenmiller’s 2014 Wall Street Journal op-ed setting out their argument, co-written with Kevin Warsh, has a distinctly uncharitable title: “Generational Theft Needs to Be Arrested.” In it, Canada and Druckenmiller indict the nation’s growing debt burden, which “threatens to crush the next generation,” along with entitlement programs that are “profoundly unfair to those who are taking their first steps in search of opportunity.” The status quo, they write, is “tantamount to saddling school-age children with more debt, weaker economic growth, and fewer opportunities for jobs and advancement.”

Thomas Friedman applauded the Druckenmiller-Canada tour in a New York Times column with an equally provocative title, “Sorry, Kids. We Ate It All.” When the invariable senior citizen showed up at one of the duo’s campus talks to protest that they were fomenting generational war, Friedman writes, Druckenmiller “has a standard reply. No, that war already happened, and the kids lost. We’re just trying to recover some scraps for them.’”

Thomas Friedman applauded the Druckenmiller-Canada tour in a New York Times column with an equally provocative title, “Sorry, Kids. We Ate It All.” When the invariable senior citizen showed up at one of the duo’s campus talks to protest that they were fomenting generational war, Friedman writes, Druckenmiller “has a standard reply. No, that war already happened, and the kids lost. We’re just trying to recover some scraps for them.’”

Listening to Druckenmiller and Canada, and many other prominent figures heralding coming (or current) generational conflict, it’s hard not to worry about how we’ll ever survive the projected “gray dawn.” Older voters dramatically outnumber younger ones at the polls today—and the two groups’ interests can seem increasingly at odds. Indeed, it’s possible to interpret developments like Brexit and the 2016 US presidential election as early indicators of the indifference of the old to the prospects of the young.

“Demography is supposed to be destiny, and many believe the coming years will be full of animosity between generations. The perils are real, the fears and concerns legitimate. But I believe there’s another way…”

Demography is supposed to be destiny, and many believe the coming years will be full of animosity between generations. The perils are real, the fears and concerns legitimate. But I believe there’s another way—and the possibility of a far better outcome, one that could help us avoid conflict, solve problems from literacy to loneliness, reweave the social fabric in communities, and reconnect us to our fundamental humanity.

BUILT FOR EACH OTHER

The route to this more uplifting prospect is neither obscure nor abstract. It’s right in front of us, in everyday lived experience and common sense. Shift the currency from fiscal woes to emotional truths, and the result reveals something profoundly different—the needs and assets of the generations fit together like pieces of a jigsaw puzzle.

Let’s start with families. There’s probably no relationship more revered in modern life than the bond between grandparents and grandchildren. Indeed, a new book on the subject, Jane Isay’s Unconditional Love: A Guide to Navigating the Joys and Challenges of Being a Grandparent Today, just arrived in my mailbox. I put it next to Lesley Stahl’s Becoming Grandma: The Joys and Science of the New Grandparenting and several other recent volumes plumbing the depths of this bond. Stahl reports that “in various surveys, nearly three-quarters of grandparents say that being a grandparent is the single most important and satisfying thing in their life. Most say being with their grandkids is more important to them than traveling or having financial security.”

Let’s start with families. There’s probably no relationship more revered in modern life than the bond between grandparents and grandchildren. Indeed, a new book on the subject, Jane Isay’s Unconditional Love: A Guide to Navigating the Joys and Challenges of Being a Grandparent Today, just arrived in my mailbox. I put it next to Lesley Stahl’s Becoming Grandma: The Joys and Science of the New Grandparenting and several other recent volumes plumbing the depths of this bond. Stahl reports that “in various surveys, nearly three-quarters of grandparents say that being a grandparent is the single most important and satisfying thing in their life. Most say being with their grandkids is more important to them than traveling or having financial security.”

Indeed, the presence and enthusiasm of grandparents often enriches the lives of older and younger people while making life easier and better for the generation in the middle, too. The Economist magazine, chronicling the wave of grandparents helping to support their grandchildren—in many cases, actually raising them—calls this fit between older and younger “the Silver-Haired Safety Net.”

My wife, Leslie, and I have three sons, ages eight, ten, and twelve. (Yes, we got a very late start—sometimes I think we had our own grandchildren.) My own father, a doting grandparent, passed away this year, and my mother is both frail and twenty-five hundred miles away in Philadelphia. Leslie’s mother, a healthy seventy, lives an eight-hour drive away and has eight grandchildren spread along the West Coast. It’s a joyous occasion when she shows up to visit and help take care of the kids. But that happens two or three times a year at best, given the geographic distance and equitable distribution of grandparental love and assistance.

Still we’ve been fortunate. Our silver-haired safety net is located two doors down. Our quirky, engaging eighty-something neighbors, Jake and Joyce Anderson, have become quasi grandparents for our children, what anthropologists call “fictive kin.” Their own grandchildren live in Idaho and the Sierras, hours away. So they get to ply their grandparenting impulses on a day-to-day basis with our kids, and everybody is the better for it, especially our middle son, Levi, the maker in the family. He and Jake, a former aviation mechanic at the Alameda Naval Air Station, disappear on projects in Jake’s toolroom, while our youngest son, Micah, a budding numismatist, spends time with Joyce going over her foreign coins.

When emergencies arise, we know we can count on Joyce and Jake to fill the void, offering the kids an occasional safe haven after school or coming by to help when there’s a crisis. This all happens by virtue of proximity, but I suspect Jake and Joyce are a connection to a time when our block was a more communal one. They are also a connection to something deeper and more fundamental than the history of our neighborhood.

“The old, as they move into the latter phases of life, are driven by a deep desire to be needed by and to nurture the next generation; the young have a need to be nurtured. It’s a fit that goes back to the beginning of human history.”

There is significant evidence from evolutionary anthropology and developmental psychology that old and young are built for each other. The old, as they move into the latter phases of life, are driven by a deep desire to be needed by and to nurture the next generation; the young have a need to be nurtured. It’s a fit that goes back to the beginning of human history.

For many decades, evolutionary anthropologists tried to understand why women typically lived so long beyond reproductive age in the harsh world of the selfish gene. Men could continue reproducing late in life. But from a narrow evolutionary standpoint, postmenopausal women seemed superfluous—until an anthropologist from the University of Utah, Kristen Hawkes, developed the grandmother hypothesis, based on her research studying hunter-gatherer tribes in Tanzania and Paraguay. She found that older women played a critical role gathering food and caring for their daughters’ children, thus enabling the longer gestational period that separates humans from most other species. In short, the role of grandmothers served as a critical missing link. If not for them, we likely wouldn’t have evolved in the way we did or ended up living so long.

For many decades, evolutionary anthropologists tried to understand why women typically lived so long beyond reproductive age in the harsh world of the selfish gene. Men could continue reproducing late in life. But from a narrow evolutionary standpoint, postmenopausal women seemed superfluous—until an anthropologist from the University of Utah, Kristen Hawkes, developed the grandmother hypothesis, based on her research studying hunter-gatherer tribes in Tanzania and Paraguay. She found that older women played a critical role gathering food and caring for their daughters’ children, thus enabling the longer gestational period that separates humans from most other species. In short, the role of grandmothers served as a critical missing link. If not for them, we likely wouldn’t have evolved in the way we did or ended up living so long.

Alison Gopnik, a child psychologist at the University of California, Berkeley, argues that the evolutionary role of grandmothers in caring for children “may actually be the key to human nature.” Meanwhile, Stanford psychologist Laura Carstensen, a preeminent scholar of later-life development, comes to similar conclusions about the grandmother hypothesis, arguing that older people are essential to future generations and the well-being of the species.

The echoes in the work of these two giants of developmental psychology who focus on opposite ends of the age spectrum are striking. After years of research, they came to similar conclusions about the essential connection between generations. So I asked Carstensen, a good friend, about the fit. She immediately raised an important question: Can the critical role of grandmothers and the benefits to children extend beyond the African savanna—and beyond older and younger people who are blood relations?

I wanted to know her take. “After so many decades of research on development across the life course,” I asked her, “what do you think?” Carstensen’s answer was immediate and affirmative. She described older people as a potential “cavalry coming over the hill” when it comes to meeting the needs of young people today. And she added that proximity is a key to realizing this promise. In other words, it helps to have a Joyce and Jake two doors down.

“We have a deeply rooted instinct to connect in ways that flow down the generational chain. And we have a set of skills—patience, persistence, and emotional regulation, among others—that, study upon study shows, blossom with age.“

I know what she means. Older people—I should say “we”—often have the time and numbers. We have an impulse toward meaningful relationships that grows as we realize fewer days are ahead than behind. We have a deeply rooted instinct to connect in ways that flow down the generational chain. And we have a set of skills—patience, persistence, and emotional regulation, among others—that, study upon study shows, blossom with age. When it comes to cavalries coming over the hill, Carstensen points out, it’s older people you want on those horses.

But, again, what does all this mean for us today, when gathering roots for grandchildren may not be the best and highest use of grandparent time? How can we tap the vast and largely underused talent of the older population (of men and women) to support the next generation in ways that fit contemporary realities? How can we do so within families but likewise across them and into the broader community?

In short, how can we adapt the grandmother hypothesis to the modern-family world?

Get your copy now!

THE RIPE MOMENT

There’s evidence that the modern-family world may be ready. Despite all the negative headlines and kids versus canes rhetoric, polling shows remarkable warmth between the generations. Surveys reveal an extraordinary degree of mutual respect, most especially between boomers and millennials. And an overwhelming majority of older people say that the opportunity for future generations to prosper is important or very important to achieving America’s promise, putting it on par with individual freedom, the work ethic, and free enterprise as priorities.

“We’re witnessing an incipient movement today of older people who are connecting with younger ones, standing up and showing up for the next generation, and resisting the mandate to go off in pursuit of their own second childhood. Instead of trying to be young, they’re focused on being there for those who actually are.“

Attitudes are changing, but more importantly, behaviors are, too. We’re witnessing an incipient movement today of older people who are connecting with younger ones, standing up and showing up for the next generation, and resisting the mandate to go off in pursuit of their own second childhood.

Instead of trying to be young, they’re focused on being there for those who actually are.

I’ll offer Stanley Druckenmiller as Exhibit A. The sixty-five-year-old investor has not only become a public voice for the next generation; he’s helped spearhead a billion-dollar philanthropic fund, Blue Meridian Partners, to invest large sums in education and social programs for young people living in poverty.

And Druckenmiller is hardly alone. For more than thirty years, I’ve crisscrossed the country, meeting older people without Druckenmiller-sized bank accounts who are acting on the same desire, to leave the world better than they found it. And I’ve spent years—no doubt influenced by my experience with Gil Stott and a string of older mentors who followed—trying both to encourage this behavior and to create new ways for those in the second half of life to support younger people.

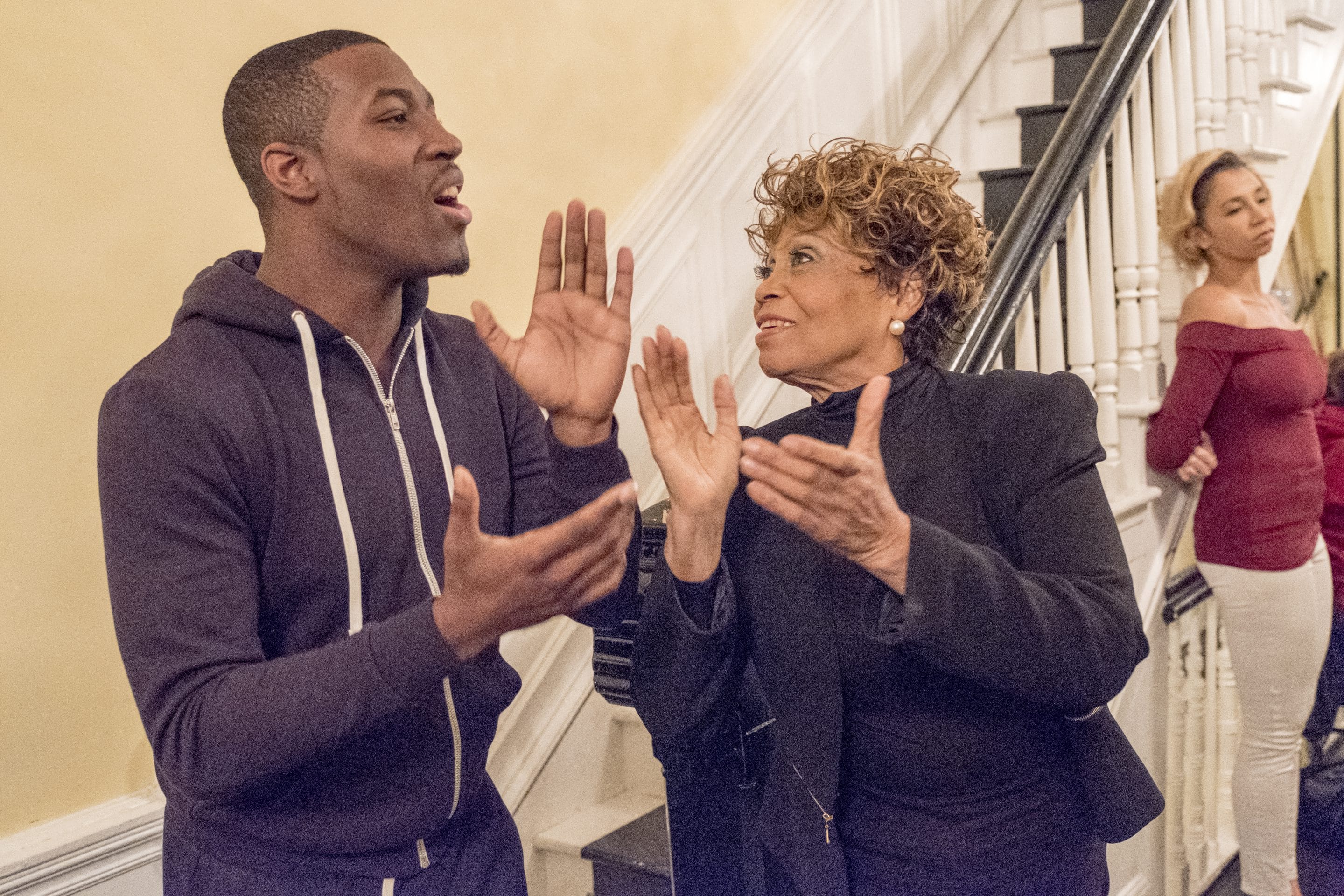

One of my inspirations is Cherry Hendrix, a woman I first met in 1986 in a Northeast Portland, Oregon, elementary school, in a rough-and-tumble neighborhood known for its high concentration of former inmates. Hendrix had moved to Portland from her native Alabama during World War II, part of the large migration of southern African American women to the ports and factories in the West and North. They came to support the war effort, and Cherry was, essentially, Rosie the Riveter.

After the war ended, Hendrix remained in Portland, managing a modest living until she retired at sixty and launched a second act in the Foster Grandparents program—a national vehicle for bringing more people over sixty into the lives of children from low-income backgrounds. When I met her, she’d been a foster grandparent for more than a decade, tutoring elementary school students for twenty hours a week in return for a small stipend.

After the war ended, Hendrix remained in Portland, managing a modest living until she retired at sixty and launched a second act in the Foster Grandparents program—a national vehicle for bringing more people over sixty into the lives of children from low-income backgrounds. When I met her, she’d been a foster grandparent for more than a decade, tutoring elementary school students for twenty hours a week in return for a small stipend.

The constraints of the tutoring relationship had gotten Hendrix thinking: How could she better connect with the children and gain their trust? An avid bowler, Cherry decided to start a bowling league for the kids. She talked to the management at Interstate Lanes in Portland, where she participated in a Jacks and Jills league. They agreed to provide shoes, gratis. Then the seventy-year-old woman handwrote forty-three permission slips for the children to bring home. Soon a thriving league was under way.

Hendrix, known as Grandma Cherry to the kids, would go on to become an inaugural member of Portland’s Experience Corps—part of a national program I helped start (now run by AARP) that provides tutors and mentors who are over fifty to about thirty-one thousand children a year in 279 schools. Cherry “retired” from Experience Corps at the age of ninety-four and lived to ninety-nine, leaving five grandchildren, ten great-grandchildren, three great-great-grandchildren, and hundreds of other kids, now adults, whose lives she touched.

Women and men like Cherry Hendrix are doing a lot more than saving a few scraps from the table. They are deeply engaged in the lives of children, showing up day in and day out to provide caring, connection, and support. And they’re getting an enormous amount out of these relationships themselves.

I know it’s easy to dismiss Cherry Hendrix and others like her as marvelous outliers, heartwarming exceptions. But I’m convinced that these individuals are far from exceptions. They are the protagonists of another story, a tale of resilience that contrasts sharply with the zero-sum, old-versus-young, demography-as-despair narrative. It’s a tale that is of growing significance today.

COMING FULL CIRCLE

This book is the chronicle of a nascent movement that has the potential to make the more-old-than-young world work, both for society and for individuals of all ages, not only right now but into the future. It’s the story of Cherry Hendrix and so many others who are showing us the way forward, bringing into focus the power of older people investing in the next generation—and finding purpose, health, happiness, and even income while doing so. This book is an account of why their efforts matter, why they haven’t yet realized their full potential as a movement, and what we can do to turn that around.

“This book is the chronicle of a nascent movement that has the potential to make the more-old-than-young world work…“

The stakes couldn’t be higher as we choose between two paths forward, prompted by the new demographics and the arrival of our profoundly multigenerational future—one characterized by scarcity, conflict, and loneliness; the other by abundance, interdependence, and connection.

As you may have guessed, this account—this quest—is as personal as it is professional for me. Earlier this year, I turned sixty myself. If becoming a nation of more older people than younger ones is a shock to our national self-identity, I can say that crossing this Rubicon is a shock to my own self-conception. I was always the young person who admired and advocated for older people—at least that’s how I saw myself.

This journey has been a surprise for me in more ways than one. I came to my vocation focused on kids, not older people. But I quickly discovered that the only resource big enough to help solve the problems facing the next generation is the older one. Back then, a world with more old than young seemed like a distant prospect. And I was a young person myself.

For the past three decades, I’ve worked to engage older people’s untapped talents in helping to alleviate young people’s unmet needs. This is an account of the lessons I’ve learned along the way, the older mentors who have supported me throughout, and my transformation from a younger person to one of them. Or, I should say, again, one of us.

In many ways the ensuing chapters are a sequel to The Big Shift, a book I wrote eight years ago to make the case that a new life stage is taking shape between the middle years and anything resembling true old age—a development akin to the creation of adolescence a hundred years ago. This emerging period has been described as “a season in search of a purpose.” This book is about how we might find that purpose by investing in the next generation, forging a legacy that endures, and leaving the world better than we found it.

“The stakes couldn’t be higher as we choose between two paths forward, prompted by the new demographics and the arrival of our profoundly multigenerational future—one characterized by scarcity, conflict, and loneliness; the other by abundance, interdependence, and connection.“

The humorist Fran Lebowitz has remarked that she always believed older people were a kind of ethnic group—that they had been born old! And that she was part of a different group, one born young. Until she realized that if we’re lucky, we all become part of that seemingly other tribe.

Now that I’m here, I have so many more questions than answers. How will I go from being the recipient of love and support from a string of elders, starting with Gil Stott, to being one of the givers, a master of what matters? What lessons can I learn from the mentors I’ve been lucky enough to have? Can I be as good at giving as receiving? How does one make the time and the shift?

The ensuing chapters are as much about coming to grips with these personal questions as they are about wrestling with the question of how we make the most of a (much) older society. That’s because, of course, the personal and societal questions are one and the same. How we answer will determine not only our collective ability to navigate the multigenerational world already upon us but also our individual ability to find the keys to happiness and fulfillment in the second half of life.

The ensuing chapters are as much about coming to grips with these personal questions as they are about wrestling with the question of how we make the most of a (much) older society. That’s because, of course, the personal and societal questions are one and the same. How we answer will determine not only our collective ability to navigate the multigenerational world already upon us but also our individual ability to find the keys to happiness and fulfillment in the second half of life.

And the time for answers is now. No extensions allowed.

Named one of the year’s best books on aging well!

How to Live Forever tops the Wall St. Journal’s list of “Best Books of 2018 on Aging Well.” It’s the perfect holiday gift for friends and family — and, since all author proceeds go to Encore.org, buying copies is a great way to support our cause. So get a copy at your local bookstore or order online today!

Spread the word

Let family, friends and colleagues know about How to Live Forever with these sample social media posts, enewsletter copy and graphics.

Start the conversation

How to Live Forever brings many personal and societal topics to the fore — longevity, age segregation, purpose, generativity, innovation, mentoring and more. Here’s a discussion guide to help you start conversations anywhere — at work or the library, your place of worship or your book group, your service organization or the place where you volunteer, your local senior center or your neighborhood civic association.